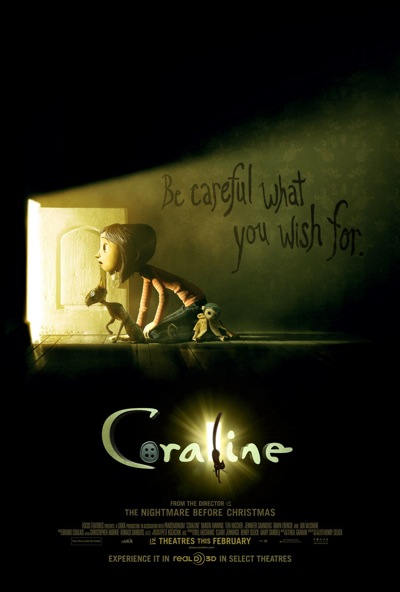

[Image via IMP Awards.]

Friday the 6th of February I took the opportunity to see the newest adaption of a Neil Gaiman story into a movie, Coraline. This movie, while shown in 3D and marketed towards children, is not a children’s movie. It is very dark and frankly, at times it can be scary, but that isn’t to say that the lessons of the movie are not lessons children should learn. The essence of the movie (plot and psychological concepts) not withstanding, I think this movie (and obviously the novel it was based on) can illustrate a lot about the role of architectural discourse and place in surreal post-modern fiction. Now, I won’t pretend to have references or anything as researched as that, but I wanted to share my take on the movie and how both concepts of the home and domesticity and the architecture of place are used to illustrate the lessons of the film.

First, the use of visual iconography in relation to the overall appearance of the Pink Palace helps convey the mood of the story. In the real world it is weather-beaten and badly in need of cosmetic repairs; the shutters are falling, the paint is peeling and the external attic stairs are precarious at best. This gloom spreads to the garden as well, where the plants all appear dead. At first, in the other world, it is a perfect victorian cottage. The colors are bright and cheery, the shutters and trim are well maintained and delicate, and the stairway to the attic appears sturdy and stable. In the other garden, the plants spring to life and are filled with a neon electricity at the presence of Coraline. When the world starts to unravel all of these elements are turned around. First the garden turns dark and vicious, then the external stairs come loose form the house, and lastly the colors start to fade from the entire world and with them the details of the house’s exterior. The same parallels exist in the interiors as well, what was is really in need of some love and attention in the real world is at first shiny and perfect and then decays in the other world. This treatment of the visual language of architectural elements help to portray Coraline’s opinions of both worlds: her world seems banal and lacking compared to the life she left, while the other world is exciting and fun, until its trap-like nature starts to become visible, which in effect helps further the movie’s message that nothing is perfect and to beware that which is too good to be true. In the end, Coraline and all of the houses inhabitants appear to have taken the chore of its maintenance and care into their own hands. Further showing that the world is what we make of it.

The second topic that I think bears exploration is the movie’s exploration of smooth and striated spaces. In Coraline’s traveling through the hole in the wall she journeys through a smooth space – a space where there is no relative measure of comparative movement. This journey of considerable distance appears to put her exactly where she left, except this is another version. The audience can interpret this either as she has not moved at all, and is in essence in a world within her house, or she has travelled a great distance to find herself in a parallel (albeit created) world. This is held in comparison to when Coraline tries to run from the other mother to the well. She is obviously moving through striated spaces – spaces where this is a means of relative comparison of movement, yet she effectively winds up exactly where she started. She did not “run around the world” as the cat states, instead she has been effectively transported back to her origin, but facing the other direction. This counterintuitive interpretation of striated spaces helps to emphasis the cat’s warning about the other world, that it is not what it seems.

A third architectural reading from this move can be taken from the treatment of the hearth. In semiotics, the hearth is a symbol of not only warmth, but also of family, comfort, creation, and the concept of the home. In the other world, the hearth is none of these things. The hearth is located in the other mother’s room, and in essence is an element of destruction and separation from family. The other mother imprison’s Coraline’s family in a snowglobe on her hearth, thus removing her from her family, she burns the gazing stone in the hearth removing a method of Coraline finding her way home. In addition, the other mother’s hearth spreads an eerie glow across the room and generally emanates a feeling of discomfort. This contrast is not ideal though. In Coraline’s real world, the hearth is a relatively sterile item. Family life does not revolve around it, and it does not play a large role in early parts of the movie. Its main function here is housing the accoutrements of family, the snow globes and other collectibles that have accumulated throughout the years. This is the closest the hearth comes to playing a traditional role in Coraline’s world. Yet this is important to illustrate that her world is not perfect, but it is still her; world.

One of the last things that I find intriguing from a space planning point of view is the little door in the wall. Coraline’s mother suggests that it may have once linked to one of the other apartments in the Pink Palace. This is an odd statement. From the way space is shown in this movie, the house is divided into three apartments: the Basement, the main floor and upstairs, and the attic. If this door ever connected to any other space it would have had to be a means of vertical connection, a la a dumb waiter. Yet those are mounted mid wall at grasping height, not along the floor. In addition, the rest of the house (save the hearth) appears to be a standard wood American Victorian house, if that was the case, what would be the explanation for brick to be present behind the wall. If this was a flat in England than the presence of brick would be more plausible. All told, this seems to be an architectural way of making the audience (or at least those that are architecturally inclined) aware that something is not quite right with this door.

Bearing all of these things in mind, I would love to watch this movie again and look for further means in which spatial coding and architecture are used to tell the story and influence the audience.