Frank O. Gehry, there is no other practicing architect who has as much name recognition amongst laymen and who can cause such distress amongst architects. With his two recent projects (the Princeton Lewis Science Library and an addition to the Art Gallery of Ontario) open to the public there has been much talk about the stylistic dichotomy between them. Phillip Kennicott, in an article examining Gehry’s body of work, wrote in this past Sunday’s Washington Post:

as observers attempt to sum up his career and project his legacy, there is a growing sense that his most acclaimed work, buildings made in the style of Bilbao, have turned out to be dead ends. Rather than open up new possibilities for the architect, they seem to have left him in a rut. And as his most recent projects suggest, Gehry’s best work today may be his least “Gehryesque.”

Yet, I have to wonder if the critique’s that have been written about these two buildings and their relationship to his work as a whole have missed the forest through the trees.

The problem with analyzing Gehry’s work is that too often critics fall into the trap of comparing his buildings as individual works against the sum total of his previous work. The problem with this is two fold: first, many of his buildings are being built out of order, i.e. they were designed long before the financing, permits, and land deals came through; second too often critics are distracted by the finishes and forms of his buildings an do not look at the concept behind the skin. These issues can be mitigated if the some total of his work to date was explored not as a collective of past explorations, but rather as one large art exhibition with a common theme.

At first this idea must seem outlandish; what relationship can there be between the offices for Chiat-Day, the Gehry House, Bilbao, the Lewis Library and the Art Gallery of Ontario? The answer is volumes and skins. In everyone of these buildings (and dare i postulate, all of his buildings) Gehry has been experimenting with ways to create and mask volumes through the application or removal of a skin. The Chiat-Day office building is an exploration of volume, two large mostly rectangular prisms are separated and obscured through a binocular shaped volume (an ode to Po-Mo if there ever was one). The skin of this building was classical in nature and snug to the volumes, but still a skin; it was allowed to create non habitable spaces in an attempt to both create sculptural forms and indicate its non-structural nature; it is punctuated by punched openings which allowed views into and out from the interior volumes.

Where Chiat-Day is about volume, the Gehry house is all about skin. The house is a pretty standard house volume, but the skin has been removed in places and reconfigured in others. The drywall has been removed form the stud walls to create views of the wall structure, and a chain link fence which normally serves as a landscape skin of sorts is repurposed to skin the roof terraces.

Bilbao (and the Disney Concert hall) take this skin and volume dynamic to the next stage. The volume is wrapped in and obscured by an opaque artificial metal skin, which has been peeled back and removed in some areas to provide light and occupant access into the spaces. In the case of the Disney Concert Hall, the skin has been held back from the building in some areas to provide views of the structure, much like the Gehry house, but instead of revealing residential construction, here the armature of the metal skin and the steel support columns of the interior volumes are revealed.

In the Lewis Library (and in many cases the Stata Center) there is both an artificial skin present which is held off of the volumes as well as a very classical skin which is allowed to fit snug to the volumes. But here, the volumes are neither rectilinear Cartesian Spaces like Chiat Day nor programmatic blobs like Disney and Bilbao, instead they are deconstructed trapezoidal prisms which are not informed by the shape of the program they contain . In this way the volume skin dynamic is becoming a Russian nesting doll. The skin wraps the volume (and in some areas is broken by the volume) which in turn wraps the program elements but all are done in such a way as to reveal that the moves are deliberate and non derivative from function, i.e. these building are the antithesis of the Modernist creed – form only casually follows function.

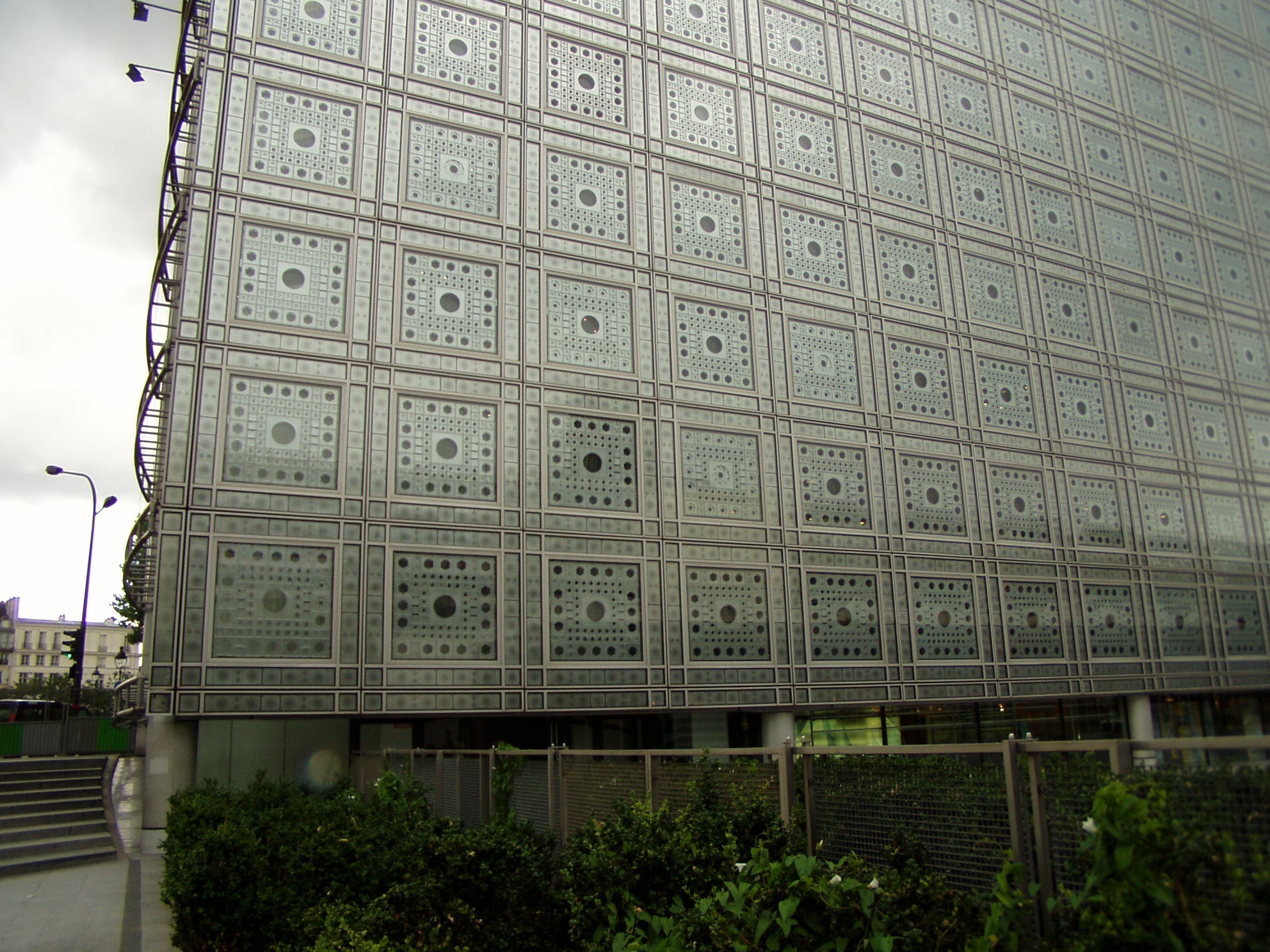

Lastly, in the Art Gallery of Ontario, we see a more restrained skin being applied to a volume – here it is a glass wall instead of an aluminum panel. In this exploration, Gehry has taken the opportunity to create a skin which reveals the volume and structure inside through its very nature. No longer does the skin act as a barrier to the public eye, creating structured views and concepts of the building, instead it is additive to the building, opening the space and structure up for observation.

Phillip Kennicott states that he believes that “[w]hat Frank Gehry needs now is a new chapter, a last act, a purifying of his life’s work into something final and thoughtful.” I have to disagree; when viewed as i have demonstrated Gehry’s work is already thoughtful and quite pure. While it may not be the kind of legacy that stays alive with Joe Public, I feel architectural academics already have plenty to discuss. I have no doubt that future work of his will further explore ways in which volumes can interact with artificial skins, and in doing so inform the occupant and observer about the structural nature of the building. While not the culmination of his work, when viewed as part of a logical and deliberate exploration of volumes and skin you can see how this building is very “Gehryesque.”